The Art of Ikat Weaving in Sumba: History, Motifs & Meaning

- August 23, 2025

- 5 minutes

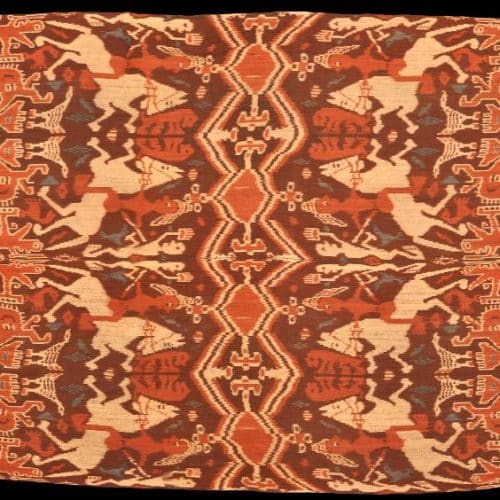

The Art of Ikat Weaving in Sumba: Culture, Craft, and Meaning

On Sumba, cloth is more than clothing: it’s memory, status, prayer, and livelihood—carried on the warp and weft by generations of women.

A living history of Sumba ikat

Across eastern Indonesia’s island of Sumba (NTT province), handwoven textiles have long served as status markers and ceremonial exchange valuables—given at marriages, funerals, and other rites. The designs, techniques, and even the way cloths are paired for exchange encode local ideas about rank, reciprocity, and ancestry.

This worldview is tied to Marapu, Sumba’s ancestral belief system in which paired forces—male/female, sun/moon, life/death—are kept in balance through ritual. The same logic of balance appears in poetry, architecture, and textiles.

Related: Discover Sumba – Unraveling Marapu and the Meaning of Kabisu.

Sumba’s cloth is rooted and cosmopolitan: centuries of trade brought Indian patola, beads, and foreign motifs that were reinterpreted within Sumba’s own visual language rather than copied outright.1

Women at the loom — empowerment through making

Weaving knowledge is transmitted mother-to-daughter. Women design, bind, dye, and weave—preserving clan memory while earning income from their expertise. In modern practice, cooperatives and training programs help formalize the craft economy, improve bargaining power, and keep traditional techniques viable.2

In rural NTT more broadly, strengthening the natural-dye supply chain (e.g., cultivating Indigofera for blue) has documented potential to increase household earnings and make weaving a more resilient livelihood—especially for women.

The meaning behind the motifs (how to “read” a cloth)

Sumba textiles are famous for bold figurative imagery that encodes beliefs, rank, and history. Meanings vary by village and clan, but commonly referenced elements include:

- Horses — mobility, wealth, and prestige in a horse-centered island culture.

- Skull tree (andong/andung) — a stylized memory of pre-colonial headhunting; in textiles it can signal ancestral power and communal vitality.

- Mamuli (Ω-shaped pendant) — emblem associated with femininity, fertility, and marriage exchange; the motif appears in cloth as well as in precious metal heirlooms.

- Fauna & flora (crocodiles, birds, shrimp, etc.) — attributes and protections tied to the natural world, localized by region.

Note: Meanings can differ by village and lineage; treat any “dictionary” as guidance, not law.

Geometric patterns matter, too. Stripes, chevrons, diamonds, and checks frame the field, signal origin (East/West stylistic habits), and offer a safe space for innovation in rhythm and color. In East Sumba, the pahikung supplementary-warp technique often carries these geometric sequences (sometimes paired with warp-ikat panels), while large narrative figures typically appear in warp-ikat fields of hinggi and lau hiamba. In general, geometric order communicates balance and continuity rather than a single fixed symbol.

How Sumba ikat is made

“Ikat” refers to resist-dyeing yarns before weaving. On Sumba, makers typically bind patterns onto warp yarns (warp ikat) and then weave on backstrap or frame looms:

- Design & binding — pattern is mapped from memory and tied on the warps.

- Natural dyeing — classic colors include indigo blue (Indigofera), morinda red-brown (Morinda citrifolia), and iron/tannin mud blacks; layering/over-dyeing builds depth and nuance.

- Weaving & finishing — warps are aligned so motifs emerge crisply; finishing varies by region and purpose.

Alongside warp ikat, East Sumba is renowned for pahikung (supplementary-warp patterning). Some of the most complex women’s skirts—lau pahikung hiamba—combine both approaches (supplementary warp + warp ikat) in the same garment and are considered pinnacles of the tradition.

It helps to learn the basic cloth terms:

- Hinggi — large rectangular men’s ceremonial cloths, traditionally worn in pairs; designs often include large figurative motifs (e.g., skull trees).

- Lau — women’s tubular skirts; many (lau hiamba) are decorated with warp ikat, and others (lau pahikung) with supplementary warp; elite lau pahikung hiamba combine both.

Because natural dyes demand time, plant knowledge, and careful sequencing, high-quality, naturally-dyed pieces cost more—and should.

Weaving as livelihood — income and resilience

For many households, weaving is both heritage and income. Province-level studies in NTT show that developing local supplies of dye plants (especially Indigofera for indigo) and strengthening producer groups can raise artisan earnings and create work that fits around agricultural calendars.

At the same time, relying only on tourist demand can expose makers to shocks. Cooperatives, fair contracts, and diversified markets (local, national, and international) help stabilize income while rewarding quality and cultural integrity.3

From ritual to market (and how to buy ethically)

Not all cloths are the same. Some textiles are ritual and circulate only within customary exchanges; others are commercial and made for sale or gifting. Respecting this boundary is key to being an ethical buyer.

- Ask about dyes & yarns. Natural dyes and handspun cotton take longer and cost more—expect (and accept) price differences.

- Buy from cooperatives or trusted intermediaries that document origin, techniques, and maker payment.

- Avoid commissioning sacred/ritual designs for fashion or décor; choose non-ritual patterns and contemporary pieces instead.

- Mind provenance. Receipts, maker names (with consent), and technique notes keep value with the community.

- Support dye ecology. Producers who cultivate or source indigo/morinda/tannins sustainably help keep the color ecosystem alive.

Preserving ikat for future generations

Sustaining Sumba ikat means sustaining knowledge, plants, and fair markets. Regional initiatives—from artisan organizations that mentor natural-dye processes to museum and academic documentation—help keep techniques, meanings, and materials accessible for the next generation.

Ultimately, the cloth endures because it is useful and meaningful—worn, exchanged, mourned with, celebrated with—and because women continue to lead the art with skill and pride. The most powerful support readers can offer is attention matched with respect: pay for quality, learn the meanings, and let ritual remain ritual.

Glossary (at a glance)

- Ikat — resist-dyed yarns woven into patterned cloth (Sumba: mainly warp ikat).

- Hinggi — men’s ceremonial cloth, often worn in pairs.

- Lau — women’s tubular skirt; lau hiamba (warp ikat), lau pahikung (supplementary warp), lau pahikung hiamba (combined).

- Pahikung — supplementary-warp technique producing crisp geometric/figurative bands.

- Mamuli — precious-metal pendant emblematic of fertility and exchange value; also a textile motif.

- Andung (skull tree) — powerful motif referencing ancestral vitality and older warfare histories.

Editor’s note on sensitivity: Motif meanings and ritual use differ by region and clan; the interpretations here are guides, not fixed rules. Economic observations synthesize NTT-level research on craft and natural dyes; where implications are extended to Sumba, they are framed as province-level context.

From textiles to traditions, Sumba is a place where culture is woven into daily life. If this story inspired you, continue your journey on our Discover Sumba page — your gateway to exploring the island’s people, landscapes, and living heritage.